Saturday, September 30, 2006

GEN, SC, ST, or OBC?

![]() Recently, a very special friend of mine politely undressed me regarding my nonchalant viewpoint on the use of labels and titles. It isn't so much that I flippantly apply such distinctions to people, or groups of people for that matter, but rather that I simply don't think much about them. I believe the luxury that I have never had to ponder over them much is due primarily to the place in society that I was born into -- that of a middle-class white male.

Recently, a very special friend of mine politely undressed me regarding my nonchalant viewpoint on the use of labels and titles. It isn't so much that I flippantly apply such distinctions to people, or groups of people for that matter, but rather that I simply don't think much about them. I believe the luxury that I have never had to ponder over them much is due primarily to the place in society that I was born into -- that of a middle-class white male.

"Semantics are vital," I was reminded. "The ways we talk about things are the ways in which we create them both within us and in the world. If we walk around being uncareful of our language, we reinforce and support problematic political and social discourses."

As work has been a bit slow lately, I've been investing more time in chai breaks and in discussions with my coworkers. After more than two years in rural Guatemala conversing on little more than agriculture and sex, I find the dialogue here to be inimitably more refreshing. Being at an institute of higher learning, topics of the more intellectual variety are regularly fostered, such as history, culture, science, and politics (Side note: we do not speak much of agriculture here, but sex talk is fair game and quite common).

I stopped in with one of the senior researchers to chat about the various malaria studies currently in progress in the area. He detailed the rationales behind the studies; the studies' objectives; the field site locations and characteristics; the methods of data collection and analysis; and the target populations. He referred a bit to the plethora of tribal people around here and then threw out the word "backward". I assumed his employment of the word was similar to the fashion in which it is cavalierly tossed around in the US: as a descriptor, a pejorative fashion of portraying a group that was, in his mind, lacking in social and/or cultural advancement and achievement.

![]() As he repeated it a few more times, I motioned for him to pause, “Did you say backward?" I asked.

As he repeated it a few more times, I motioned for him to pause, “Did you say backward?" I asked.

"Yes... The backward castes."

"Achcha (I see)... So which castes are the backward castes?"

"That is it. The backward castes. Other backward castes."

To him I replied, "Achcha" and to myself I thought, "What a dick jerk!"

It is important to note that his (or the prevalent Indian) use of the word 'backward' is not necessarily the same as ours. Regardless, I still felt a bit uncomfortable and shortly thereafter excused myself.

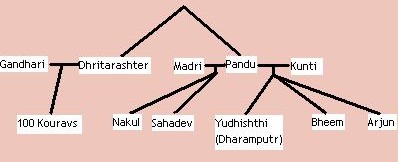

About a week later, I was perusing some of the questionnaires used in local malaria studies to see what information was being solicited. Date. Participant ID number. Name. Age. Caste/Tribe. Under caste/tribe, there were a few options for boxes to check: SC, GEN, ST, and OBC. I approached one of my friends here and inquired as to what each of the abbreviations represented.

![]() GEN = General Castes

GEN = General Castes

SC = Scheduled Castes

ST = Scheduled Tribes

OBC = Other Backward Castes

"Is 'Other Backward Caste' a term that you just use here or is it widely accepted in India?" I asked.

Her response was startling: "Mandate 340 of the Constitution."

The caste system in India is believed to be some 3,000 years old. The ancient Hindu society was initially divided into four exhaustive, mutually exclusive, hereditary, endogamous (in-marrying), and occupation-specific Varnas (translated into English as caste via the Portuguese word casta which means breed or race).

According to the Vedas (Hindu scripture), the progenitors of the four castes sprang from various parts of the body of the primordial man -- he who was created by Lord Brahma from clay. Brahmans (priests) originated from the mouth to provide for the intellectual and spiritual needs of the community. The Kshatriyas (warriors) were forged from the arms to bestow protection. Vaishyas (merchants and landowners) sprang from the thighs and were entrusted with the care of agriculture and commerce. The feet gave rise to the Shudras (artisans and servants), who were entrusted with the care of all manual labor. Conceptualized later was a fifth category, the Ati Shudras or Untouchables, unto whom was bequeathed all menial and polluting work related to bodily decay and dirt.

As the economy became more complex, the varna system morphed into the jati system, with jatis sharing the same basic characteristics as the varnas. The difference in the systems is that jatis are not exact subsets of varnas; and there has also been considerable regional variation in the evolution of specific jatis. Thus, a jati may be considered "backward" in one state but not in another.

Caste divisions are not as dichotomous as they may appear, but the distinctions are simplified by the nature of the available data.

![]() The general castes (GEN) are comprised of those that belonged to the three highest classes in the varna system: Brahmans, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas.

The general castes (GEN) are comprised of those that belonged to the three highest classes in the varna system: Brahmans, Kshatriyas, and Vaishyas.

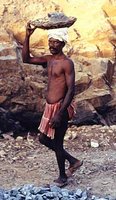

The scheduled tribes (STs), that make up around 7-8% of the population, are socially and economically marginalized tribal people known throughout India as Adivasi.

The scheduled castes (SCs) are those formerly categorized as untouchables and are composed of 16-17% of India’s population.

The other backward castes (OBCs) form a very large and heterogeneous category (~30% of the population) and are remarkably close to SCs in terms of social and economic "backwardness". Hence, the distance between the SCs and OBCs only manages to understate the chasm between the top and bottom tiers of the caste hierarchy.

Although there are laws banning caste-based discrimination, violence habitually occurs across the country. It must also be noted, that not all forms of violence are obvious or overt. For example, land is owned almost exclusively by members of the dominant castes which allows them to economically exploit lower-ranking laborers and artisans.

In recognition of caste-based inequalities, the Indian government initiated affirmative action as a remedial measure. Every state now has a quota for the SCs and STs that implies reserving 22.5% of seats in the legislature, government-sponsored educational institutions, and public sector jobs. The present-day quotas do not offer opportunities for those belonging to an OBC.

Recently, the government declared its desire to set aside an additional 27% for OBC members as well as a few other disadvantaged groups. The announcement led to widespread backlash from many higher caste Hindus, especially those attempting to matriculate into the Indian Institutes of Technologies (IITs). Graduates of these prestigious engineering colleges have, in recent years, flooded Silicon Valley and triggered India's information technology boom.

![]() I have tried my best to get first-hand information regarding the caste system, but many Indians are loathe to speak of it.

I have tried my best to get first-hand information regarding the caste system, but many Indians are loathe to speak of it.

A couple of days ago, I mentioned to some colleagues here that I imagined that lower caste members here were poorer and suffered from worse health outcomes. Some very effortlessly agreed. Others nodded a bit more begrudgingly. A third contingency excitedly stated that it used to be like that but wasn't any longer, and then made it clear that the conversation had reached its end.

Tensions have greatly increased recently due to the proposed quota increase. The blogosphere offers a taste of some voices that may not be suitable for an even-keeled discussion.

A sample:

"I look around me and all I see angry voices protesting, dissents, strikes, suffering of services, all of which tarnishes the image of the India I would like to belong to, one where I am who I made myself into and not what I was born as!"

Another:

"I am, in no way a snob or elitist. I have friends from all walks of life, colleagues who may or may not be an OBC/SC/ST, teachers who I admire and respect for their wisdom rather than where they came from, neighbors with whom I share festivals and events and meals with no thought spared to ‘Are they the same caste as me?’... I honestly couldn’t care less what caste you belong to!" (Editor's note: What caste do you think he belongs to?).

My turn:

I think it safe to say that if you deserve something based on your skills, abilities, and talents, then you should get it. The problem with that, however, is that too many people have been marginalized for too long so that the playing field is no longer equal.

Those in power and those who continue to make up the privileged sections of the country's society have inhibited the empowerment process by denying education and knowledge to the lower castes.

It ain't black and white, though it kind of is. Sound familiar, America?

.jpg)

.jpg)