We quickly blow through introductions, sit down, and begin to stare around the room. He picks up the phone, says something in Hindi, hangs up the receiver, and proceeds to pick his teeth with a sewing pin. A strange silence ensues. A minute or so later, the actions are repeated: Phone, Hindi, pin, silence. And then again. The only variation I notice, is that with each ensuing phone call his voice grows successively louder. I try a few times to interrupt the awkwardness with questions pertaining to his data, but he doesn't seem interested.

We quickly blow through introductions, sit down, and begin to stare around the room. He picks up the phone, says something in Hindi, hangs up the receiver, and proceeds to pick his teeth with a sewing pin. A strange silence ensues. A minute or so later, the actions are repeated: Phone, Hindi, pin, silence. And then again. The only variation I notice, is that with each ensuing phone call his voice grows successively louder. I try a few times to interrupt the awkwardness with questions pertaining to his data, but he doesn't seem interested.

As time passes, the awkwardness morphs into a confusion that borders on discomfort. Just as I am considering the possibility of excusing myself, the door opens.

“I hear you like coffee,” he offers. “And I ask them make it strong.”

I struggle to think of a better way to dispose of the silence than the proposition of satisfying my three-week long coffee fix.

“Theek hai. Theek hai.” (is good), I reply, wishing that my Hindi brain would allow me to dispense a superlative to properly articulate my gratitude.

Within two minutes he finishes his drink. I hasten to follow suit.

He moves over toward his computer and pulls up a chair along side where I then seat myself. He proceeds to open up Excel file after Excel file -- a veritable treasure trove of malaria data –- wasting little time explaining the plethora of letters and numbers flashing before our eyes. A good ten minutes later, he leans back in his chair, sighs, and smiles.

“I do not boast. I am very good researcher. But... but now I have these numbers and I do not know what to do.”

I spent the majority of that afternoon, and many that have followed, helping Gyand Chen familiarize himself with the world of statistics. Our working relationship has developed into a pattern: I expound on the appropriate statistical tests to use, employment of them with various statistical packages, and the interpretation of the outputs; and he feeds me copious amounts of “coffee” (see: Nescafe) and illuminates interesting facts and facets of Indian history and culture.

Toward the end of our third session together, he asks me if I know Arjun. I furrow my brow a bit and run through a full catalog of new faces in my head. I had met so many people in the last few weeks and I was sure one of them must have been the Arjun of whom he spoke. I replied that I wasn’t sure.

“You are like Arjun…” he begins.

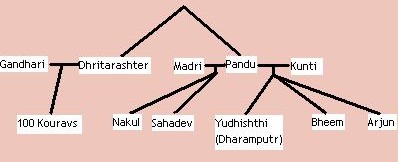

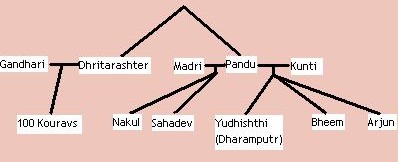

“Dhritarashter and Pandu were brothers. Dhritarashter was born blind and although he was the elder, he was compelled to forfeit his claim to the throne on account of his physical defect; Pandu thus became king. Whereas Dhritarashter married Gandhari, Pandu selected two wives -- Kunti and Madri. Gandhari was so devoted to her husband that she bandaged her eyes and chose to remain voluntarily blind for life. She became the mother of the Kouravs, 100 in total. Kunti had three sons and Madri two.

”One day while hunting, Pandu accidentally killed the wife of a sage, who became enraged and cursed Pandu that should he ever have relations with a woman, he would die instantly. Pandu renounced his crown for the life of a hermit and went to the jungle with his two wives, Kunti and Madri. One day, Pandu could not resist temptation, had intercourse with Madri, and died. Madri immolated herself and walked into her husband's funeral fire leaving behind her two sons, Nakul and Sahadev, in custody of Kunti with her three sons, Yudhishthir, Bheem, and Arjun. On Pandu's death, Dhritarashter became the king and the five sons of Pandu -- the Pandavs -- grew up in the guardianship of Kunti. The five Pandav princes were educated along with Kourav boys under the patronage of Dhritarashter. They were taught the art of archery as well as various techniques of warfare.

”Yudhishthir, the eldest of the Pandavs, was so righteous that he was anointed with the name Dharamputr. Bheem was a giant in physical strength. Arjun was handsome and the most skilful archer. Dharamputr was the beloved of the people and being the eldest among the 105 princes, was the natural heir to the throne. Duryodhan, the eldest of the Kouravs, however, was jealous of the Pandavs and tried every means to destroy them. When Yudhishthir was proclaimed king, Duryodhan could not sit quiet and watch. Duryodhan hatched numerous plans plan to kill the Pandavs, one of which eventually forced the five brothers, along with their mother, to escape into the jungle. After their departure, they did not return to the palace but instead roamed about in disguise as priests. Everyone, including the Kouravs, believed them to be dead.

”During that time, they heard of the beautiful Swayamvara of Droupadi. The qualification to marry her laid in the extraordinary skill of hitting a moving target with a bow and arrow. Arjun won easily. The spectators, undoubtedly surprised by the bowmanship of the priest, eventually discerned that it was in fact Arjun. The Pandavs were discovered.

“Arjun took his bride to their hut and called to his mother to come and see what he had brought. Instead of doing so, she answered back: ‘My dear children, whatever it may be, share it among yourselves’. Hence, Droupadi became the wife of all five Pandavs.

“The kingdom they received as dowry was divided into two parts. Naturally, the better half was seized by the Kouravs. Still, the Pandavs built a wonderful city in their own half and named it Indraprastha. Duryodhan, watching the increasing prosperity of the Pandavs, could contain his fury no longer. He openly challenged Dharamputr to a game of dice in which the losers would live in the forest for thirteen years without any claim to the kingdom. The last year of their exile was to be spent incognito; should they be discovered, the thirteen year cycle would begin anew. Sakuni, deceit in human form and uncle of the Kouravs, played for them. Inevitably, Dharamputr lost.

”In the thirteenth year of their exile, the Pandavs and Droupadi went to the palace of the king of the Viratas and stayed there as servants. Duryodhan made frantic efforts to discover them and eventually concluded that the Pandavs must be in the Virata country. The Kouravs then attacked the Viratas. The Pandavs took part in the battle, but by the time they were recognized as Pandavs, the time limit of thirteen years had already passed.

“The hundred Kouravs and their supporters were on one side, and the Pandavs and theirs on the other. The armies arrayed themselves for war.

“The Kouravs had devised a formation that only Arjun knew how to defeat. Shortly before the war is to begin, Arjun has second thoughts about his participation and leaves the battlefield. His brothers become disconcerted and are unsure how to proceed…”

“So you see,” Gyand Chan continues. “You are like Arjun.”

I struggle to make the connection and I think he notices.

“You see… I can enter all this data into the computer, but I do not know what to do with it. I can penetrate the formation but then I can not get out. If I can not get out, what happens? We lose the war.”

As I sit back and attempt to draw parallels between data analysis and one of the most famous battles in Indian history, he lifts up the receiver and barks something in Hindi.

A moment later, the door swings open. This time I know what's coming.

.jpg)

.jpg)